Discover why embracing structure in cinematic storytelling doesn’t restrict creativity, but unlocks it.

Ready to transform your cinematic narrative?

Dear Storyteller,

The idea that “too much structure makes a story predictable and dull” is the cinematic equivalent of saying “verse, bridge, chorus” is boring. Tell that to storytellers like Dylan, Springsteen or Del Rey.

It’s a notion that isn’t just wrong; it’s lazy and smacks of hubris.

The real issue with a our stories isn’t that too much structure is killing them — it’s that we have far too little structure plus we have a half-baked premise, an undercooked idea, small themes and the lack of courage to dive deep into the mechanics of what makes a story tick.

We’re about to dismantle this myth and rebuild it with some much-needed, brutally honest perspective.

Structure is not the antagonist, it’s the mentor

Let’s debunk this idea that structure somehow shackles creativity. Structure is not a prison; it’s a blueprint. The Eiffel Tower, the Coloseum, the Pyramids — these marvels weren’t slapped together with a ‘let’s just see what happens’ approach. They were meticulously planned, their structural integrity ensured before the first piece was put in place.

Storytelling is not too different. We storytellers are architects too. The structure of a screenplay is what holds the bloody thing together, what keeps it from collapsing into a mushy heap of random scenes and incoherent and unsatisfying character arcs.

When someone says ‘too much structure makes a story predictable,’ what they’re really saying is ‘I don’t know how to use structure effectively.’ Field’s three-act structure, the hero’s journey, even Blake Snyder’s oft-maligned “Save the Cat!” beat sheet — they aren’t the problem. There is great stuff in there.

I would argue, however, that there is not enough structure in them — and that what writers need —especially less experienced writers — are far more rules.

Predictability isn’t about structure, it’s about execution

Let’s address the elephant in the room — predictability. The truth is, there’s nothing inherently wrong with predictability. Every genre has its conventions, its rules, its expected beats. If you walk into a romantic comedy and don’t expect the leads to get together at the end, you’re either delusional or new to the genre.

Predictability in the hands of a skilled writer doesn’t feel predictable. It feels inevitable.

Take Christopher Nolan’s Inception. The film is structured to within an inch of its life. You can practically set your watch by the plot points. But does it feel predictable? Hell no. It feels like a high-wire act, a ticking clock, with a narrative that’s always one step ahead of you. The structure is the backbone, but it’s the execution; the premise, the characters, the stakes, the gigantic themes—that keep you on the edge of your seat.

Blaming structure for predictability is like blaming a map for not taking you on an adventure. The map is just a guide. The journey—the excitement, the tension, the surprise—comes from how you traverse that map, how you navigate the terrain. It’s about the choices you make along the way, not the fact that you’re following a path.

The illusion of ‘too much structure’

Let’s talk about this idea of ‘too much structure.’ What does that even mean? It’s a vague and nebulous concept that’s more about personal taste than any real storytelling flaw.

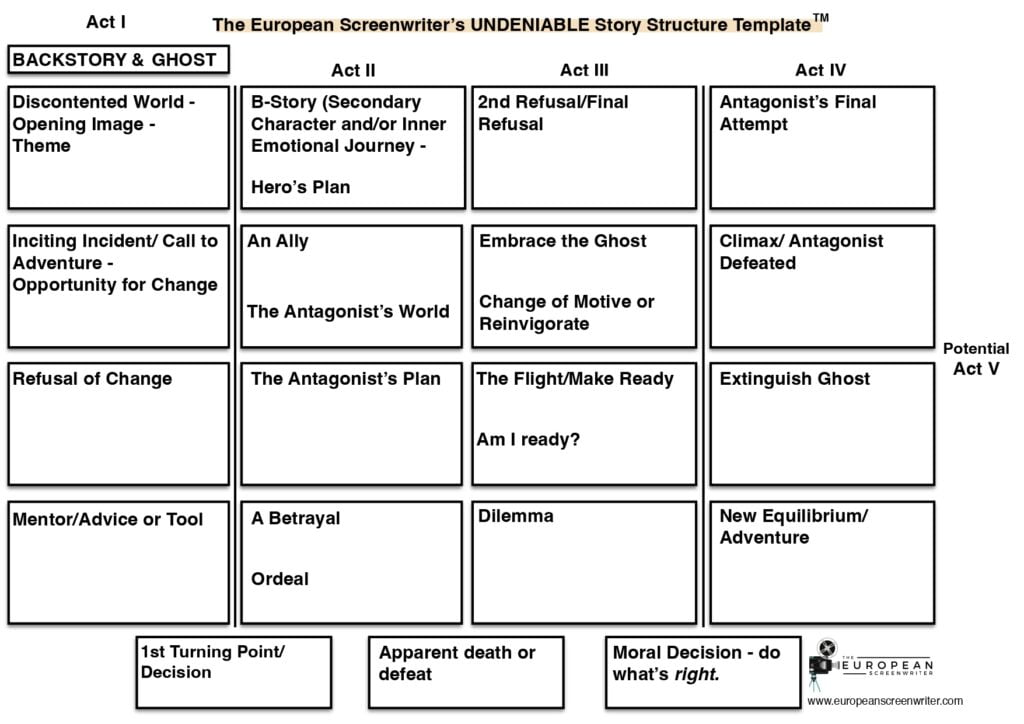

I use a very detailed structure template these days — I call it the UNDENIABLE structure template. I will introduce it to the world very soon.

It’s the structure I used to pen GUNN, the screenplay that snagged me Gold Prize at the prestigious 2023 PAGE Screenwriting Awards, and DIRTY BOY, which made it all the way to a Gala Screening at 2024 Cannes after securing full funding within just a year.

GUNN is ostensibly an action-horror movie with a very linear plot — roughly looking like: ‘Man rescues daughter from her kidnappers.’

So how did it win such a prestigious award amidst such obviously strong competition?

Well firstly, the screenplay was structured very intricately with every possible turning point and reversal mined for the utmost drama.

But also, the protagonist is a punch-drunk Scottish fisherman with seemingly supernatural powers and the villains that he is going to rescue his daughter from are a band of Odin-worshipping, neo-Viking meth-heads whose lair is an abandoned oil-rig in the middle of the North Sea. It’s an almost absurd premise, but when it is realised within a taut structure, it’s elevated, bold and exciting. For me, this is the key; have big, bold, surprising characters and situations, but structure them into an intricate paradigm.

PAGE Screenwriting Award Judge: ‘The writing is very, very strong — in places I would call it beautiful. One of the best scripts I’ve read so far this year.’

Writers need more structural rules, not fewer

When films are criticised for ‘too much structure,’ what they’re often reacting to is a lack of originality in other areas — flat stock characters with hackneyed motivations, uninspired, on-the-nose dialogue, or a premise that’s been recycled more times than last year’s memes.

They’re mistaking the symptoms for the disease. The real issue isn’t an over-reliance on structure; it’s an under-reliance on imagination. A tightly structured story with a fresh premise, dynamic characters, and snappy dialogue? That’s the gold we’re mining for.

A loosely structured story with the same old tropes and clichés? That’s just a mess and an insult to anyone who paid to watch.

Here’s where we really rock the boat: Writers don’t need fewer structural rules—they need more. More detailed, more rigorous, more demanding. Structure isn’t just about keeping your story from falling apart; it’s about pushing your story to be the best it can be. We need to create solid frameworks that challenge us to innovate, dig deeper, to refine your ideas until they shine.

A jazz musician doesn’t become great by ignoring scales and chords; they become great by mastering them so thoroughly that they can break the rules with intention. The same goes for screenwriters. Master structure, know it inside and out, and then use that knowledge to break expectations, to play with form, to create something truly original within the framework.

In Pulp Fiction. Quentin Tarantino didn’t ignore structure; he mastered it. He understood the rules so well that he could rearrange them, chop them up, and still create a narrative that’s compelling, surprising, and utterly satisfying. The film’s non-linear structure isn’t a rejection of traditional storytelling—it’s an evolution of it. And it works because Tarantino didn’t just throw out the rulebook; he rewrote it with a deep understanding of what makes stories work.

The need for a more exciting premise

Now, of course a detailed, rigorous structure isn’t worth squat if your premise is dull. And this is where so many writers fall flat. They focus so much on hitting the beats, on sticking to the structure, that they forget the foundation of any great story: the premise.

You can have the most perfectly structured screenplay in the world, but if your premise is bland, your story will be too.

A truly exciting premise is one that grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go. It’s a concept that sparks the imagination, that makes you sit up and say, ‘I need to see how this plays out.’

I challenge people I mentor to come up with the most outlandish premise they can — my belief is that cinematic stories need to be bold and unforgettable from the very beginning. And when they’ve developed that bold premise that maybe even scares them a little bit, they tend to find that when its constrained within a very taut structure magic happens.

Structure helps you make the most of that premise. It’s the foundation that allows the wildest ideas to soar into the clouds

DIRTY BOY, my first feature, which was invited to a gala screening at Cannes earlier this year, uses the exact same structure template that I used to write Gunn — but they are very different films. What they have in common are grand themes, a complex protagonist and truly fearsome villains (wait until you see Graham McTavish and Susie Porter tearing up the screens in Dirty Boy — a very frightening pair indeed!)

In THE MATRIX, the premise: a world where reality is a simulation, is mind-blowing on its own. But it’s the bold premise guided along within the rigorous structure that makes it a classic.

The hero’s journey, the carefully plotted reveals, the escalating stakes, they’re all part of a meticulously crafted structure that takes that killer premise and turns it into a cinematic landmark. Without structure, The Matrix would just be a jumble of cool ideas with no coherence, no impact. With structure, it’s a masterpiece.

The case for more structure, not less

Structure is not the enemy. The lack of structure, the misuse of structure, the misunderstanding of structure—these are the real villains of cinematic storytelling.

This notion that too much structure makes a story predictable and dull is not just wrong; it’s a cop-out, an excuse for lazy writing. It’s easier to blame structure than to admit that perhaps your premise isn’t as exciting as you’d initially thought, or that your characters aren’t as complex as they could be.

Writers don’t need fewer rules; they need more. They need more detailed structural guidelines, more rigorous demands on their creativity, more challenges to push them beyond the obvious and into the extraordinary. They need more exciting premises; ideas that are so compelling that they demand a robust structure to bring them to life.

So dear Storytellers, let’s embrace structure, master it, and then use it to create something that truly defies expectations. Because at the end of the day, it’s not about how many rules you follow—it’s about how well you use them to create something unforgettable.

Follow me — next week, I will dig deep into the UNDENIABLE Screenplay Structure that I have used to create my successful screenplays.

Doug Rao